Why Chris Blackwell Decided to Sign U2 to Island Records

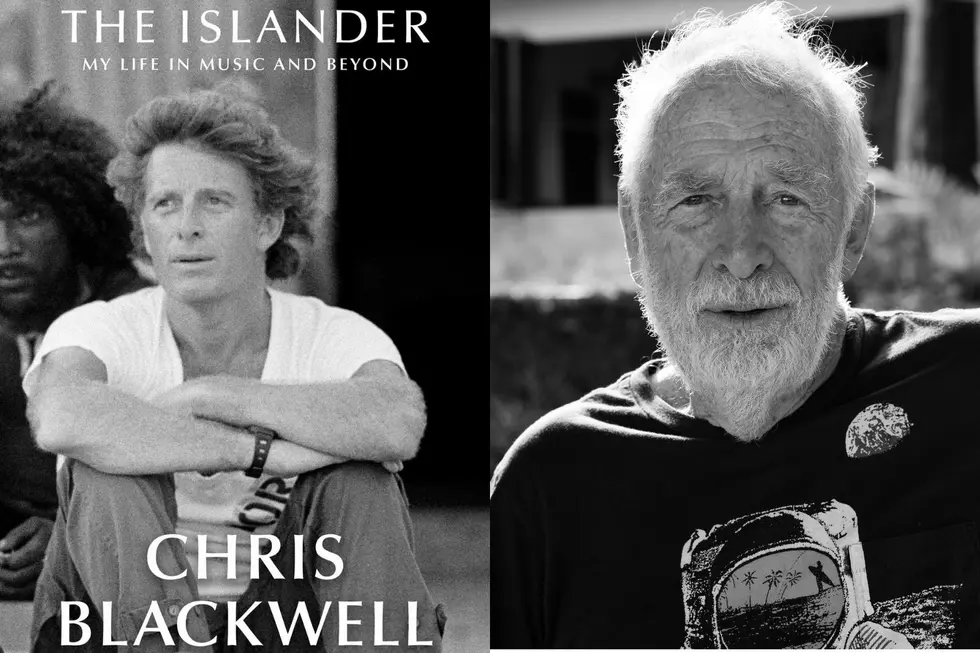

Chris Blackwell is the founder of Island Records, one of the largest independent record labels in history. Along the way, he's produced and released albums from world-renowned acts like Bob Marley, U2, Cat Stevens, Robert Palmer, Traffic and countless others.

Believe it or not, all that success started on the advice of a Jamaican soothsayer.

Blackwell, who was born in London but grew up largely in Jamaica, had worked a wide array of jobs by the time he was a young man: real estate management, record distribution, and as a production assistant and location scout for the 1962 James Bond film Dr. No. (Blackwell's mother was a friend of Ian Fleming's.) After the shoot wrapped, producer Harry Saltzman offered him a full-time job. Unable to decide, Blackwell visited the soothsayer. "The cards don't lie," Blackwell remembers her saying. He made up his mind to stay in the music industry.

Decades later, Blackwell would be considered by many as the man responsible for introducing reggae music to the mainstream via his small but mighty independent label, which eventually grew to host some of the most influential names in rock and pop music.

Blackwell's new memoir, The Islander: My Life in Music and Beyond, (written with Paul Morley), revisits the stories behind some of these musicians and their relationship with Island Records. The legendary record producer recently spoke with UCR about a few key players.

(Blackwell will be signing copies of the memoir at Rough Trade Records in New York City on June 16. Details can be found here.)

I think probably my favorite section in the book is the one about Nick Drake, who's always been a very shrouded kind of character in music history. It's a shame he didn't get much recognition when he was living.

Well, there's an overall sadness to it because he's such a soft, gentle genius, in a way, you know? When I first met him, he'd come to see me, to see if I might be interested to sign him. At that time, he was in university, and at that time, I was right in the middle of kind of hard rock 'n' roll – which was Traffic, the band and I had called Traffic, which had become, you know, really quite strong — Steve Winwood was the lead singer on that, and another band called Spooky Tooth. But I was more in sort of heavy, like, rock 'n' roll, and he was really gentle. I told him that I really liked him, I really liked his music, but I didn't feel I could really help him at that time, as I was really focused on what I was doing. I said to him, "But come back in six months," you know? And he came back in six months, and nothing much had really changed in six months. It wasn't that I didn't think he was talented; it was clear that he was talented. He was really special, just his aura. [Drake signed to Island at age 20 and released three albums with them, though none gained much notoriety until after his death from an overdose at age 26.]

In the book, when you describe meeting Bob Marley and the Wailers for the first time, you mention how you immediately recognized they had potential, but that a lot of your Island colleagues thought you were crazy for signing a group you had never heard live, and that didn’t fit into any traditional “rock” or “pop” group. What was it then about them and their music that made you stick with your gut?

You know, I started with Jamaican music. The first record I ever produced was in Jamaica, a singer I heard at a concert, and at the end of the concert, I went backstage and said, "I think you're terrific. I'd love to record you." He'd never recorded before and he said "I'd love to do that." And then another guy was standing nearby and he said, "Well, what about me? I'd love to do that." And then another person said, "I'd love to do that." [Laughs.] So I ended up recording three different artists which were attached to Jamaican rhythm and Jamaican feel, and the first three of them all went to No. 1. I had, you know, three records in the Top 5. So, that's how I started, and that's what my base knowledge or skill set was, or whatever.

It sounds like you had a lot of faith in your choice at that moment, even if the surrounding atmosphere — the recording industry, the radio industry, your colleagues — weren't necessarily as faithful.

Yeah, well, for the Marleys situation, when the Marleys arrived, they arrived on their way back, trying to get their way back to Jamaica. They'd been stranded because their manager had sent them to do some work in Scandinavia and that didn't really work out so well, and they flew back from Scandinavia to London, but they didn't have the airfare to get back to Jamaica. So really, they were there to see me, to see if I could help them get back to Jamaica – and maybe they could do a record for me or something like that. That's how I first met them, but I felt that they were very charismatic, all three of them. I felt that, you know, I could do something to help them in a way, guide them, because my roots was Jamaican music. So I knew the language. I understood that music really well.

Then there's the opposite of that: You write later in the book about your first early impressions of U2 and that “if I had just heard them on a demo tape, I would have passed.” But you saw them perform live in a little venue, and you saw Bono’s energy and the whole group’s attitude and decided to sign them. Can you speak a little to that?

I went into the club, and there were probably about 10 people in the club, and then the band came on and it opened up to about 15 people. [Laughs.] So it wasn't that they were well known or anything at all, but it was just a club that their manager set up so I could listen to them. When I saw them playing and their passion, I really started to feel differently about them from right at the beginning. Then later on, as you heard other songs, that same passion was really there – that added a huge amount for me. But also, very importantly, was the fact that they had a manager, somebody actually wearing a suit. I was always pretty sloppy with just flip-flops and such, but he was there in a suit. In the case of U2, I was really impressed in this little club, with maybe 17 people in it [and] this man, very well dressed and very clearly a serious businessman. I thought, "Wow, well, if he's there to do this. You can see their drive and their passion for what they were doing." I didn't feel the music personally, because, again, my roots [were in] Jamaican music and that's all about bass – the bass line, you know? And in their case, it was more the higher-ranged guitar and stuff like that. So I really decided, without any question, to sign them because of the reasons I just told you – a manager and their passion.

Have there been moments in your career that, if you had the chance, you’d go back and handle differently?

Yes, there would be one or two. You know, sometimes there can be a bunch of people who each want to do their own thing. So the bass player wants to play a different feel than what the guitarist is doing, that kind of thing. That's something that could happen a lot. But then, on the other hand, when there was a band where they were just, like, locked together – that each one knew what their role was, and performed them – then you would feel that's something that could really happen.

Something that stands out to me in the book is the relationship you had with a lot of the artists you worked with. There seemed to be a solid level of trust and understanding between the two parties. Why do you think that was?

Because I trusted them. I genuinely trusted them. I think if somebody offers trust, you know, providing they're honest [laughs], that is the best thing you can have really – because you have a working relationship where you can say to the person, "I think you could do that a little better" or "You could do that a little different." But you're doing it for them; you're not doing it for yourself. You're doing it for your wanting to help with some guidance. If they don't feel that, then they're right too. If you give some guidance and they don't feel it, they shouldn't necessarily take it.

U2 Albums Ranked

More From KMGWFM