How Jay-Z, OutKast and A Tribe Called Quest Forecasted Hip-Hop’s Future 20 Years Ago

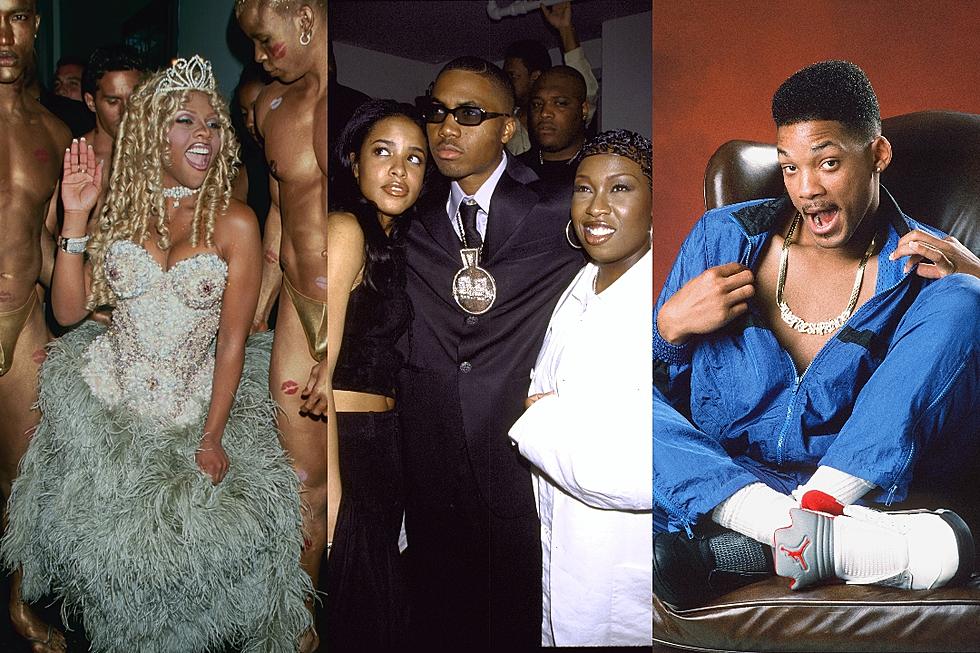

We are far beyond Peak Nostalgia at this point, but 1998 was quite the year for popular culture. The Bill Clinton/Monica Lewinsky scandal dominated headlines. Michael Jordan gave us The Last Shot. Rush Hour was released. Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa were engaged in a home run race. TRL premiered. And all of this took place before the summer ended. It was a landmark year in music, too—so momentous, in fact, that Billboard and Pitchfork devoted entire weeks to retrospective coverage of it. But on Sept. 29, 1998, one week into the new season, something exceptional happened in hip-hop. While that is the date of this publication’s historic “The Greatest Day in Hip-Hop History” photoshoot, conducted by the inimitable Gordon Parks, there was something else that took place within the genre, and that it occurred on the same day is some remarkable kismet which makes that title all the more fitting.

This other event took place in record stores (back in the days of The Wall’s lifetime guarantee sticker) or wherever you could purchase music in physical form. This was back when The Event Release wasn’t a surprise, but even if you spent the summer of 1998 tracking these release dates in magazines and on posters and billboards, you had no idea what was on the horizon. Five albums were released that day: A Tribe Called Quest’s The Love Movement, Jay-Z’s Vol. 2...Hard Knock Life, OutKast’s Aquemini, Black Star’s Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star and Brand Nubian’s Foundation. The last two have been overshadowed. Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star was a breakthrough, launching both artists' solo careers. Meanwhile, Foundation marked the most adored iteration of Brand Nubian’s first album together since 1990’s One For All. But The Love Movement, Vol. 2...Hard Knock Life and Aquemini stand out because they capture hip-hop in transition.

At the time, The Love Movement served as A Tribe Called Quest’s farewell. Conversely, Vol. 2...Hard Knock Life and Aquemini represented ascendant moments for Jay-Z and OutKast. This divergence was pivotal in all of their careers, but, more importantly, for hip-hop as a whole. The moment, which took place in one of hip-hop’s banner years, was a snapshot of the genre’s future.

For all intents and purposes, The Love Movement was a formality. Most fans (and everyone who’s seen Michael Rapaport’s 2011 documentary Beats, Rhymes & Life: The Travels of A Tribe Called Quest) know A Tribe Called Quest essentially ended in the wake of 1993’s Midnight Marauders. The Love Movement, like its predecessor, 1996’s Beats, Rhymes & Life, found Tribe retreating from the sound that defined its first three albums. The upside there is the role the album played in the rise of the late J. Dilla, who is credited on more than half of it, including the last great Tribe record of the 1990s, “Find a Way.” Prior to his death in 2006, Dilla built a catalog that ultimately made him one of the most esteemed and influential producers in hip-hop history. You don’t get a producer like Knxwledge without Dilla as a forebearer, but Dilla’s work with Tribe, particularly on The Love Movement, helped him blossom into one of the greats. The album was a passing of the torch.

After carving out a very distinct place in hip-hop as its everymen during the 1990s, the group found itself without a place or purpose as the decade drew to a close. There was no new ground to chart; nothing to say—not as a unit, at least. So in hindsight, The Love Movement paled in comparison to the Tribe standard because it felt like an obligation from a group that had exhausted itself and each other. But even as they stepped away, the artists they raised, like Kanye West and Pharrell Williams, pushed what they mastered in different directions, further eliminating hip-hop’s binaries during the 2000s. And one artist in particular, a frequent collaborator of both Kanye and Pharrell who actually entered the game around the same time as Tribe, realized by 1998 that creating his own blueprint was the way to achieve the success he desired.

The length of Jay-Z’s résumé often obscures the fact that his success was not at all immediate. It took him three tries to find the right balance between the lyrical brilliance of Reasonable Doubt and the commercial appeal he awkwardly reached for on In My Lifetime, Vol.1, but Vol. 2...Hard Knock Life—still his best-selling album—found him finally figuring out how to reach everyone. Jay-Z, forever self-aware, described his trial-and-error process on the single that made him a superstar, “Hard Knock Life (Ghetto Anthem)”: “I gave you prophecy on my first joint and you all lamed out/Didn’t really appreciate it, ‘til the second one came out/So I stretched the game out…” Jay-Z’s ability to study trends and understand his audience has been integral to his sweeping mega success; Vol. 2 was the first glimpse of the artist-meets-enterprise future that awaited.

“I found the mirror between the two stories—that Annie’s story was mine, and mine was hers, and the song was the place where our experiences weren’t contradictions, just different dimensions of the same reality,” he explains in his 2010 autobiography, Decoded, of the album’s title track and breakout single, which samples the classic musical Annie.

By matching Annie’s mainstream rags-to-riches story with his own, Jay-Z found his connection to the masses. The ghetto anthem reached the coastal elites because Vol. 2 spoke to everyone. The right mixture of radio (“Can I Get A…” and “Nigga What, Nigga Who”) and street records (“Money, Cash, Hoes,” which still got radio spins, “A Week Ago” and “Reservoir Dogs”) drew new legions of fans without alienating old ones. For the next decade and change, Jay-Z owned the popular vote by utilizing a formula The Notorious B.I.G. basically patented. His evolution from lukewarm, to hot, to mogul was instrumental in him not only becoming one of the most powerful figures in popular culture, but hip-hop becoming the most popular music in America.

Vol. 2 is a case study in marketing, as Jay-Z made himself more accessible through distilled lyrics and production that deviated from the presiding sound of 1990s New York hip-hop. A Brooklyn rapper spitting double-time over a Virginia producer’s quirky syncopation was relatively novel back then—now similar pairings are routine, thanks to hip-hop’s regional convergence. As the writer David Drake asserted when revisiting Sept. 29, 1998 five years ago, “The entire world of music became a potential backdrop for the country's most charismatic MCs.” But where Jay won by making himself easier to digest, OutKast’s triumph came by way of doubling down on their eccentricities.

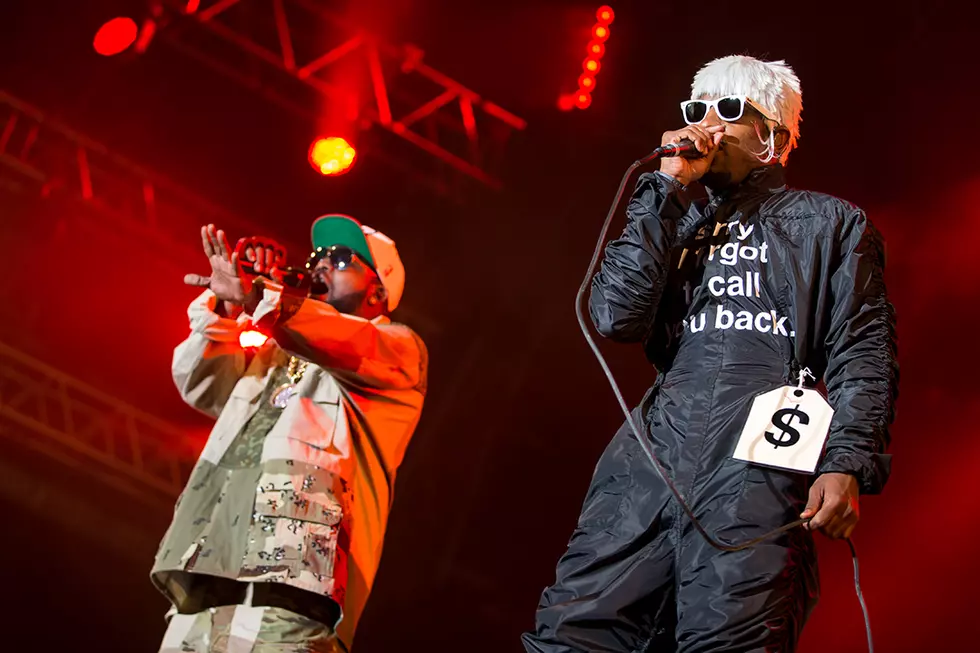

OutKast never did the same thing twice. Their relentless creativity took them beyond the Dungeon into elevators that quickly transported them out of this galaxy. Whenever it seemed like they couldn’t possibly get more ambitious, defiant or downright bizarre, Big Boi and André proved everyone wrong. Aquemini is OutKast at its most brash—and with good reason. It was a collective middle finger to anyone who booed them at The Source Awards three years prior, scrutinized their place within hip-hop at the moment or dared to question the South’s relevance to the genre. From the technology-wary prescience of “Synthesizer” to the “smokin’ word” of “SpottieOttieDopaliscious,” no album released around this time was more representative of the destabilization of late ’90s hip-hop norms or hip-hop’s transformation into something more expansive, post-Y2K.

Aquemini’s lead single, “Rosa Parks,” invoked one of the Civil Rights Movement’s most prominent figures as a symbol for the group’s quest to dismantle hip-hop’s oppressive status quo. The mid-song apex is a flurry of synchronized marching feet and hand claps layered under a kick drum and harmonica—distinctly Southern, yet still unprecedented. “Skew It on the Bar-B” brought Raekwon to the Dungeon, and he, an unmistakably New York forefather of mafioso rap, delivered a stellar verse by adapting to André, Big Boi and Organized Noize. He had to meet them where they were at. Was it the first New York/Dirty South collaboration? No, but it’s certainly one of the best and most influential. And beyond Aquemini’s immediate impact against the backdrop of 1998’s pop culture zeitgeist, it continues to ripple through hip-hop.

Unsurprisingly, Aquemini—the best and most influential album released on this historic day—has been canonized within Atlanta and the Southern hip-hop community at large. However, its impact beyond that region is a testament to its role in erasing the regional lines dividing hip-hop. You can hear it out West through Kendrick Lamar. “Swimming Pools,” “Wesley’s Theory” and “Lust” are but a few examples. You can hear it in Detroit’s own Danny Brown. His “The Return” is the spawn of “Return of the ‘G,’” where André set the record straight for anyone who had the wrong idea about him based on his appearance. Brown also explained that Aquemini showed him hip-hop could be whatever he wanted it to be. “I didn’t think rap music could go that far,” he said in 2013, later noting that it showed him “there's not really rules.” That’s what Aquemini’s remarkable “Liberation” zeroed in on: the tireless pursuit of physical, mental, spiritual and creative freedom. The space for unmoored self-expression. Not giving the slightest fuck about what anyone else thinks. And that attitude helped hip-hop evolve into its current form: exceedingly popular, increasingly difficult to categorize and better for it.

Vol. 2...Hard Knock Life, Aquemini and The Love Movement debuted in the first, second and third slots, respectively, on the Billboard 200. They pushed the biggest album of 1998, Lauryn Hill’s The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, down to No. 4. Jay-Z explained the magnitude in Decoded:

Those four albums together told the story of young black America from four dramatically different perspectives—we were bohemians and hustlers and revolutionaries and space-age Southern boys. We were funny and serious, spiritual and ambitious, lovers and gangsters, mothers and brothers. This was the full picture of our generation. Each of these albums was an innovative and honest work of art and wildly popular on the charts. Every kid in the country had at least one of these albums, and a lot of them had all four. The entire world was plugged into the stories that came out of the specific struggles and creative explosion of our generation.

The three albums released on Sept. 29, 1998—20 years ago today—had a profound impact on subsequent generations, offering a look at the range that has come to define modern-day hip-hop. Today, Jay-Z, OutKast and A Tribe Called Quest rest comfortably on the laurels of their legacies (OutKast hasn’t released an album together in 12 years; A Tribe Called Quest reunited one last time for 2016’s We Got It From Here… Thank You 4 Your Service; Jay-Z’s still going, in the studio, on tour and in the boardroom), but each act’s legacy is fortified, in part, by how the role they played in the greatest day in hip-hop’s history shaped its future. —Julian Kimble

See 60 Hip-Hop Albums Turning 20 in 2018

More From KMGWFM